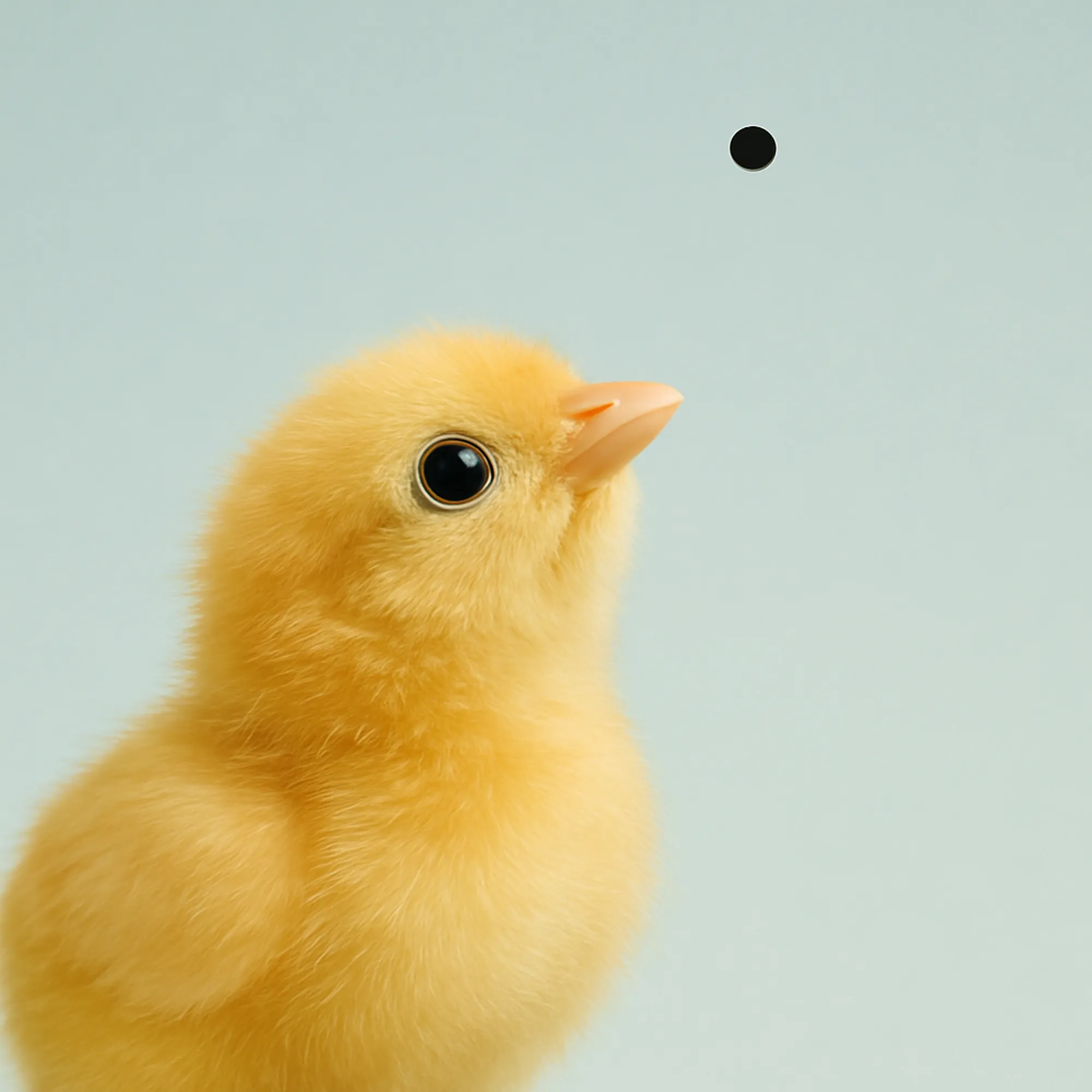

Some moments in life are so universal they seem to flow from something deeper than experience itself. Take the curious gaze of a chick, just days old, as it tracks a speck rising against gravity. Why would upward motion—so rare in nature—capture attention so powerfully in these tender minds?

TL;DR

- Brains are tuned from birth to notice when things move upward—against gravity.

- Special neurons in chicks’ brains light up for this surprising motion, linking perception to behavior.

We live on a planet where gravity is an ever-present companion, shaping how stones fall and rivers flow. For countless creatures, including ourselves, it is background music—a silent reference note against which all movement is judged. It makes sense, then, that our senses are attuned to anything that seems to challenge this rule. Animate things—animals, humans—often move in ways that defy gravity. Spotting these movements quickly could be vital, whether for finding food, staying safe, or connecting with others.

In this study, researchers set out to peel back the layers of this mystery using humble, one-week-old domestic chicks. Young enough to have limited experience with the world’s physics, these chicks offer a rare window into inborn tendencies. The scientists presented them with simple visual stimuli: some dots glided upward, against gravity; others fell downward, as expected. As the chicks watched these motions, the researchers recorded neural activity in a brain area called the nidopallium caudolaterale (NCL)—an area somewhat analogous to the prefrontal cortex in mammals, and crucial for decision-making.

At the same time, the team tracked the chicks’ behavior using state-of-the-art video and accelerometer technology, capturing tiny, spontaneous reactions that might otherwise go unnoticed. The question: Would something as basic as the direction of motion fire distinct patterns in the chicks’ brains? Would upward motion—so rare, so extraordinary—stir something special?

The answer was clear. Not only did the chicks show a strong behavioral bias, focusing more on objects that broke gravity’s rules, but the NCL lit up for upward-moving stimuli. The recordings revealed a group of neurons tuned specifically to movement direction; most responded more vigorously to upward motion. Even more striking, the collective activity of these neurons predicted how the chicks would behave—suggesting a direct link from the perception of surprising movement to real-world attentional shifts.

For humans, the finding carries a quiet resonance. Who as a child has not watched, transfixed, as a balloon lifts skyward or a bubble drifts up? Our brains, too, may be prewired to notice when the everyday rules are bent—an ancient script for detecting life, danger, or opportunity.

Speculatively, these results hint at ways to design artificial vision systems that better pick out what matters. Perhaps robotics or autonomous vehicles could borrow this recipe, keying in on the objects that behave in remarkable ways. Clinically, understanding innate visual biases might help unravel disorders where perception of animacy goes awry.

Of course, questions remain. Do these neural circuits exist in mammals, even in humans? How do they change with experience? Further research, following the upward path laid out by these chicks, will be needed to answer those questions and explore the deeper origins of our sense of the animate universe.

Sources

https://doi.org/10.1101/2025.11.24.690125

10.1101/2025.11.24.690125